Statistical Evaluation of a Fuzzing Dictionary

Intro

Fuzz testing involves several configuration parameters: seeds, dictionary, fuzz scheduling (what to fuzz), fuzz duration (how long to fuzz something), fuzz mutation (how to fuzz), fuzz sites (what portions of input to fuzz) etc. This post attempts to statistically evaluate the effect of one fuzzing parameter: dictionary. The purpose of this post is to understand if the use of a dictionary for a very specific fuzzing target (a parser) leads to significantly better outcomes, statistically speaking. The fuzzer target that this post focuses on is not really relevant: so I won’t name it. It suffices to say that this target is a run-of-the-mill parser that parses string input.

We have made the argument before that the use of dictionaries makes security testing of network parsers more effective. However, a recent paper called “Evaluating Fuzz Testing” has good recommendations for basing such judgements on basic statistical tests rather than, say, a visual inspection of the measured distributions. There are two statistical tests that are recommended in the fuzzing evaluation paper. One is a significance test and the other an effect-size test.

Significance test

Firstly, it is recommended that researchers perform a significance test (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test) in order to decide if their fuzzing optimization brings about statistically significant change in some performance metric. For people unfamiliar with even basic statistics, like me, the Mann-Whiteny U test is used to—quoting the wiki page on the topic—“determine whether two independent samples were selected from populations having the same distribution.”

My understanding of this test applied to fuzzing evaluations is as follows. Consider you propose a cool tweak to afl-fuzz that you believe will bring about an improvement in fuzz testing. For simplicity, let’s assume that the only metric you are interested in improving is “fuzzing coverage” per unit time: Lines of code that are hit by the fuzzer in some unit time (say 1 minute). So, you want to check if your tweak actually performs better than the baseline on this metric.

In order to convince a scientific audience that your tweak indeed indeed brings about a positive improvement, you need to do the following before proceeding further:

- Run the baseline fuzzer (that does not contain your tweak) “N” times (greater the value of N, the better), measuring and noting the value of the metric of interest (coverage/unit time) in each run

- You will end up with an array of measurements like so: B = [b_1, b_2,…, b_N]

- Run the tweaked fuzzer “N” times, and as before, measuring and noting the value of the metric of interest (coverage/unit time) in each run

- You will end up with an array of measurements like so: T = [t_1, t_2,…,t_N]

- Compute the Mann Whitney U test p-value for the arrays

BandT- This can tell you if the performance numbers for the tweak show statistically significant divergence from the performance numbers for the baseline

Now, you have two “populations” (arrays, B and T) of independent samples (independent because each run is independent of the other) of coverage numbers.

We do not know the distribution of either population; actually this is not important to us.

What we are interested in is checking whether the distributions differ.

Specifically, we assume that it is equally likely that a randomly selected value from one population is less than or greater than a randomly selected value from the other population; this is called the null hypothesis.

We are interested in proving or disproving the null hypothesis.

Getting back to the topic of fuzzing evaluations, we are interested in disproving the null hypothesis that the performance measurements for the baseline and tweak have the same distribution, because if they do, the tweak did not do anything particularly interesting.

The p-value computation is a standard way of quantitatively checking the validity of the null hypothesis.

A p-value is essentially the probability of falsely concluding that the null hypothesis is not valid; the lower the p-value, the greater the assurance that we have correctly concluded that our tweak is indeed different than the baseline.

Traditionally, p-values of under 0.05 are considered good enough to show a statistically significant difference between two populations.

The value of 0.05 is called the level of significance: One can choose a lower level of significance (say 0.001) if one wants to be damn sure about the difference in populations.

Fortunately, there is a ready-made python function called mannwhitneyu in the scipy.stats module that outputs the p-value for two lists of numbers.

So, all you need to do is write a simple python script like so:

from scipy.stats import mannwhitneyu

# Read in baseline performance scors into array

B = [b_1,...,b_N]

# Read in performance scores for tweak into another array

T = [t_1,...,t_N]

print(mannwhitneyu(B,T))

Then you see output like so:

MannwhitneyuResult(statistic=682.5, pvalue=2.582424268793943e-26)

This tells you that the p-value is 2.58e-26 or 2.58*10^-26.

This number is a lot smaller than 0.05 so we conclude that the performance numbers corresponding to the tweak are indeed (statistically significantly) different than performance numbers corresponding to the baseline.

Although p-values of under 0.05 show that the compared populations are significantly different, it does not tell us what the quantum of this difference is.

In an extreme case, the tweak may result in a miniscule improvement (e.g., it covers 2 additional lines of code than baseline) with a very low p-value (e.g., 2.58e-26).

So although you convince people that your tweak brings about a certain improvement, the quantum of this improvement is too little to be considered scientifically interesting.

In other words, low p-values are necessary but not sufficient for our evaluation. p-values say nothing about the extent of divergence, also known as the effect size. This brings me to the second test recommended in the fuzzing evaluation paper.

Vargha Delaney’s A measure

The VDA measure can be used to gauge the extent of divergence between two populations.

Essentially, the VDA measure outputs the probability p that one population is different (greater/lesser) by computing pair-wise ordinal relationships (< or =) between samples in the two populations.

This probability p if equal to 0.5 (half) indicates that both populations have identical values (no change).

The following values of p are conventionally accepted as indicating change:

p>0.56Small changep>0.64Medium changep>0.71Big change

Essentially, if greater than 21% of pair-wise comparisons show a greater value for one population, that population is considered diverging in a big way from the other. Tim Menzies has published python code to compute VDA measure, thanks Tim. So, all you need to do to compute the VDA measure is the following:

## Fetch module from Tim Menzies' gist linked above

from a12 import *

## Create a labeled array

B_norm = ["baseline"]

## Append B values from baseline measurements

B_norm.extend(B)

## Likewise for tweak measurements

T_norm = ["tweak"]

T_norm.extend(T)

## Create consolidated list

C = [B_norm, T_norm]

for rx in a12s(C,rev=True,enough=0.71): print(rx)

The enough parameter is essentially the effect-size threshold of your choice. For the listing above, I have used the conventional big threshold i.e., p>0.71.

The python code above should output something like so

rank #1 tweak at <T_cov>

rank #2 baseline at <B_cov>

where populations are sorted in descending order (i.e., highest coverage on top) and T_cov and B_cov are means of the tweak and baseline populations.

We interpret this result as follows: There exists a big change between tweak and baseline because a lot of samples from the tweaked population show better performance (say, coverage numbers) compared to the baseline samples.

In summary, if the p-value for the measurement values corresponding to your tweak is <0.05 and has a big VDA measure, then your tweak is indeed pretty cool!

Next, I describe in what context I applied this knowledge.

Context

I was going to submit a PR to oss-fuzz to integrate a new fuzzing target. Such a PR typically contains configuration for the fuzzing engines that Google uses (afl-fuzz and libFuzzer) apart from the test case itself. One such configuration parameter is a dictionary file that contains line seperated tokens of interest that are enclosed within double quotes (see my post on inferring program input format for more details about this). Naturally, I was interested in knowing if the dictionary that I was including in the PR is actually useful.

Before I set about evaluating the usefulness of a dictionary for this specific target, I built a few simple dictionaries using tools that I had developed: Mostly this clang front-end tool called clang-sdict that performs a front-end pass on source code collecting constant string tokens used in potentially data-dependent control flow. You can find a primitive implementation of clang-sdict here.

Before finalizing on a dictionary, I wanted to experiment with a few variations and see how they fare. The nice thing about clang-sdict is that it permits several customizations: Prominently, one can tune it to focus on specific coding patterns. For example, one can add specific parsing functions (by name) and the tool extracts tokens accepted by that function. I went ahead and created three different dictionaries each with a slightly different set of string tokens. Let’s call these dictionaries “dict A”, “dict B”, and “dict C.” When the fuzzer is supplied such a dictionary, it chooses one string at random and uses it in a fuzzing mutation: Say overwrites a byte sequence with this string.

Evaluation

Now that I had these three dictionaries, I set about evaluating their “effectiveness” and “size of effect” using Mann-Whitney U Test and Vargha Delaney’s A measure. To recap, these tests answer the following two questions (in that order): (1) Is using a dictionary bring out noticeable gains in the outcome of fuzzing? and (2) How much of an effect do dictionaries have on the said outcome?

Of course, we need to fix metrics before we use these statistical tests. The metric I chose for this post is the number of lines of code covered by a fuzzing session: libFuzzer (one of the fuzzing engines behind oss-fuzz) prints the number of CFG edges covered during fuzzing. More edges covered is better than fewer edges covered (more is better).

Before I present evaluation methodology and results, some meta data about the dictionary candidates.

| Dict | Num. tokens |

|---|---|

| Baseline | 0 |

| Dict A | 120 |

| Dict B | 222 |

| Dict C | 388 |

Dict A has the fewest tokens, followed by Dict B, and Dict C.

Evaluation Methodology

The methodology centers around the following broad set of requirements with design choices shown in braces.

- Each variant should be run several times (100 runs chosen)

- Each variant should be run for the same fixed duration (5 minutes chosen)

- Reasonable metric for comparison must be used (Program edge coverage chosen)

Therefore our experiment must do the following:

- Run the baseline (no dictionary), Dict A (exp 1), Dict B (exp 2), Dict (exp 3) a total of 100 times each with 5 minutes per fuzzing session

- Log the total coverage achieved in this fuzzing session

Once we do this, we end up with a 2D array like so (numbers are hypothetical):

baseline = [b_1,b_2,b_3,...,b_100]

exp1 = [e1_1,e1_2,e1_3,...,e1_100]

exp2 = [e2_1,e2_2,e2_3,...,e2_100]

exp1 = [e3_1,e3_2,e3_3,...,e3_100]

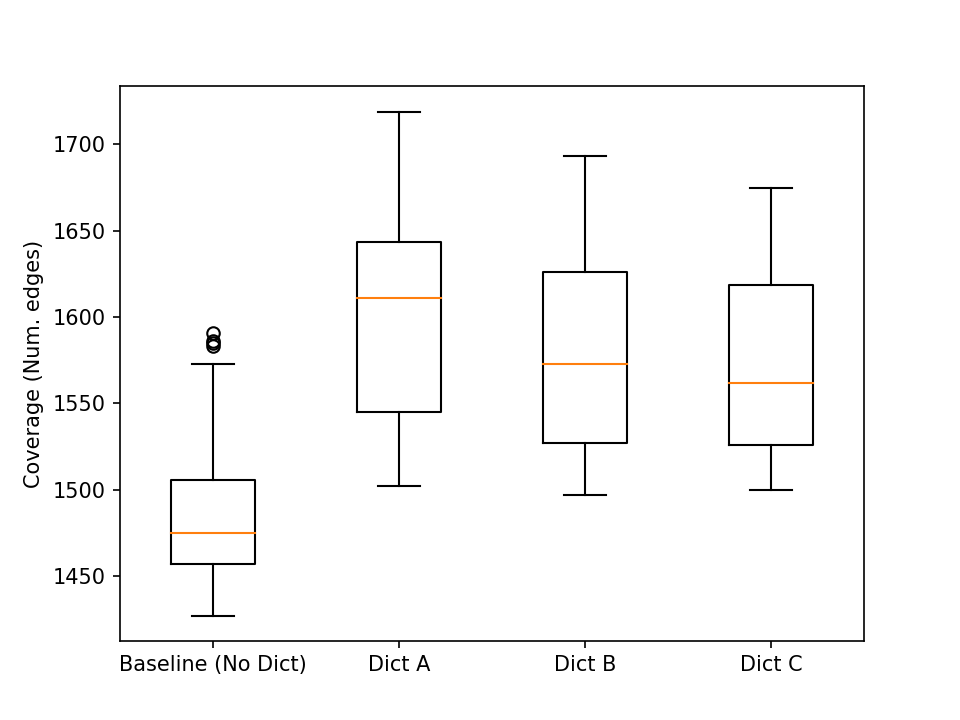

Okay, so let’s make a box-plot of them and see what they look like: Remember more edges covered, the better is the fuzzing outcome.

Y-axis is the number of CFG edges covered; X-axis is the fuzzing configuration whose coverage distribution is presented as a box plot. Okay, it (visually) appears that “Dict A” is best of all in terms of median value (the orange line that strikes through the boxes is the median of that sample set) and quartile distribution. Some more basic statistics for the test coverage populations follow.

| Name | Mean | Variance | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1488.3 | 1918.5 | 1427 | 1591 |

| Dict A | 1601.2 | 3157.2 | 1502 | 1719 |

| Dict B | 1579.2 | 2775.4 | 1497 | 1693 |

| Dict C | 1572.4 | 2374.7 | 1500 | 1675 |

Although it appears that Dict A has the highest mean (and hence the best), its high variance can be one ground to be suspicious about the claim that “it is the best.” This is precisely where significance tests enter the picture.

Mann Whitney U Test

We can check the “soundness” of the hypothesis “Dict A is different” by performing a Mann-Whitney U test on our data set.

Here’s a gist of my evaluation python script: Nothing fancy, reading coverage numbers from a log file and using mannwhitneyu function from the scipy.stats python module on the sets of acquired coverage numbers.

The p-values between different sets of evaluations are shown in the table below.

The table is to be read as (p-value between row label vs. column label); 1e-2 is to be read as 1x10^-2 or 0.01.

Since Mann Whitney p-values for the tuples (A,B) and (B,A) (where A,B are two non-identical sets of numbers) is the same, and p-value of (A,A) does not make any sense, these fields in the table have been denoted as N.A., short for not applicable.

A p-value of under 0.05 (i.e., < 5e-2) means that there is a significant difference between the means of the two sets of numbers.

| Name vs. | Baseline | Dict A | Dict B | Dict C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| Dict A | 2.58e-26 | N.A. | 2.22e-3 | 6.96e-5 |

| Dict B | 5.72e-23 | N.A. | N.A. | 19.4e-2 |

| Dict C | 5.61e-22 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

From these numbers, we can create the following “significance” table (to be read as do (row,column) populations differ significantly):

| Name vs. | Baseline | Dict A | Dict B | Dict C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dict A | Yes | N.A. | Yes | Yes |

| Dict B | Yes | No | N.A. | No |

| Dict C | Yes | No | No | N.A. |

This table tells us that

- All “Dict” populations are significantly different than the baseline AND

- Dict A population is significantly different than the rest

In some ways this is a counter-intuitive result because I would have expected more tokens (in Dict B and Dict C) result in a significant change in the outcome. It turns out it is more important to have a small set of correct tokens than a larger set: More tokens in a dictionary is not necessarily a good thing.

Bear in mind that all runs were performed for 5 minutes only, results may/will change for longer fuzzing durations. My original motivation in choosing a 5-minute fuzzing window was to get a quick understanding of the effectiveness of each of the dictionaries before sending out the PR. Having said that, given enough time and resources, we can perform the same tests after a longer time interval (say 1 hour of fuzzing) and repeat this analysis.

Vargha Delaney A12 Test

Stastical significance cannot be equated to scientifically important. The latter requires stricter evaluation of the delta in the metric: How much more improvement in test coverage did the evaluated dictionaries achieve? We know that Dict A population not only has the highest mean/median, but is also significantly different than the rest, but how much better is it? VDA test is useful for answering precisely this question.

Let’s recall that a VDA score between (X,Y) of >0.56 indicates a small change, >0.64 indicates a medium change, and >0.71 indicates a big change.

Using my evaluation gist outlined above, I compute the VDA probabilities as follows.

Again, I would like to credit Tim Menzies whose VDA implementation was the basis for these computations.

In my script, I use standard effect sizes (small=0.56, medium=0.64,large=0.71) to compute three such rankings.

Here is what I find.

Small effect ranking

- Rank 1: Dict A

- Rank 2: Dict B

- Rank 2: Dict C

- Rank 3: Baseline

In other words, Dict A offers at least small improvements in program coverage over Dict B and Dict C, which in turn offer at least small improvements in program coverage over the baseline.

Medium effect ranking

- Rank 1: Dict A

- Rank 1: Dict B

- Rank 1: Dict C

- Rank 2: Baseline

In other words, Dict A, Dict B, and Dict C are roughly the same if we require the improvement in test coverage to be at least medium (p > 0.64). Still, any of these dictionaries have at least a medium size of improvement in coverage than the baseline i.e., no dictionary.

Big effect ranking

- Rank 1: Dict A

- Rank 1: Dict B

- Rank 1: Dict C

- Rank 2: Baseline

The medium result holds even for a big effect: This means that any of the three dictionaries offer big improvement in coverage compared to the baseline.

From this we can conclude that (1) there is a small delta between Dict A, and Dict B/C; and (2) there is a big delta between Dict A/B/C and the baseline (no dictionary). In a nutshell, the “winner” is Dict A.

Conclusion

I draw the following conclusions from this work:

- Simple statistical tests provide an understanding of the significance of a change in some fuzzing parameter

- For the specific fuzzing target evaluated in this post, dictionaries indeed are very useful

Some caveats: (1) Fuzzing window chosen for evaluation was short, (2) results focus on the coverage metric and not e.g., for speed of bug finding. However, this methodology offers a scientific basis for drawing conclusions which is pretty cool. Needless to say, I added Dict A in my PR to oss-fuzz and now I can say that (in a very limited way) my PR is based on scientific evidence ;-)

Acknowledgments

Thanks to

- The authors of the “Evaluating Fuzz Testing” paper, check the paper out.

- Tim Menzies whose A12 implementation I used in this work

- My wife, Divya, for teaching me basic stats